In the presentation of the evolution of the scoring tables in the World Athletics scoring manual one encounters a section on "Developments in the Theory of Scoring Tables". I reproduce it below verbatim.

From 1920, three concepts became prominent in the theory and development of scoring tables. These have, in varying degrees, influenced all subsequent tables.

1) The fact that each unit of improvement in an athlete's performance gets increasingly harder as the athlete approaches his ultimate. This can be expressed statistically as follows: the probability of any athlete achieving or exceeding a given performance rapidly gets less as the performance rises towards the record. The score for a performance can be derived as the inverse of that probability. The resulting scoring table is progressive but, applied simply, this leads to an exceedingly progressive scoring table, and the main challenge has been to control this excess.

2) The need to be able to compare the performance of an athlete in one event with that of another in a different event or, indeed, in a different individual sport.

3) The wish to have a really "scientific" basis for any scoring system. With the growing research into human physiology and sports science, it seemed possible that a basis could be found in physiological parameters, such as heart beat, breathing rate, oxygen uptake or oxygen depletion and so on.

To me these paragraphs can only have been written in recent years, once (after various blunders) the approach to scoring had sufficiently matured. The most important point is the one I have presented stressed in bold, linking probability to scoring. In some future post of mine I will return to this point and show how a consistent theory of scoring can be constructed based on that principle.

At the end of the 20s it was becoming clear that the linear tables that were in use for 20 years were not providing a fair scoring. People were feeling that the lack of progressive character in the tables was a serious drawback. Fortunately at this point the Finnish Athletics Federation proposed a new set of tables. They were based on the work of J. Ohls and corresponded to an exponential relation between points p and performance x:

And, given the indecisiveness of the the IAAF, the new progressive tables were not used in the 1936 Olympics where the decathlon was scored with the superannuated, linear, tables. (And in case you were wondering, the linear tables were used in the 1938, 1946 and 1950 Europeans, despite the fact that the 1948 olympic decathlon was scored with the Finnish tables).

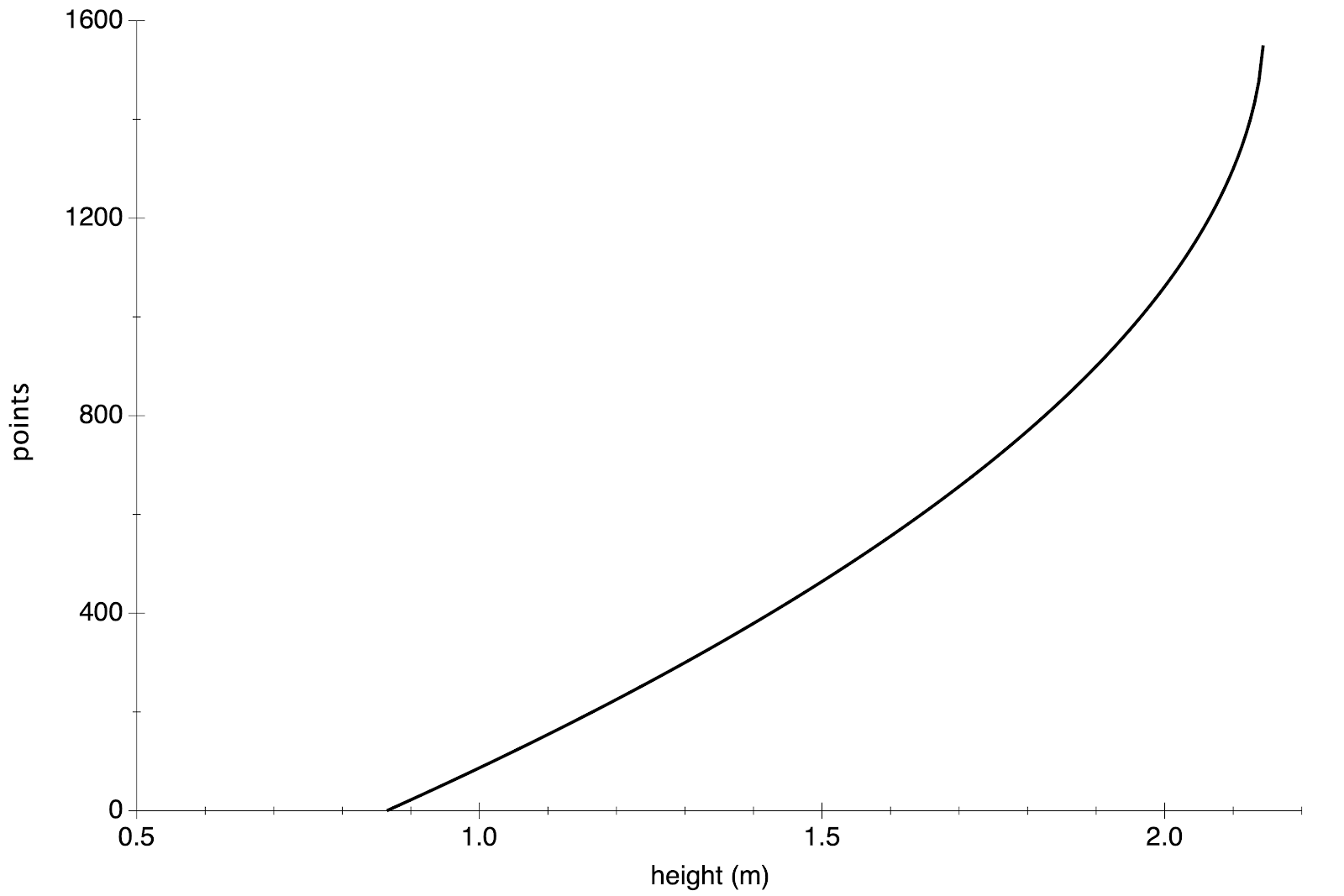

Curiously, after having used the new Finnish tables in just one Olympic Games, the IAAF decided to change them. The new tables (known as the Swedish ones) were the work of G. Hölmer and A. Jörbeck. They were approved in 1952 and were used right away in the 1952 Olympics. Curiously they were even more progressive than the Finnish tables, in fact exaggeratedly so. The scoring formula was one involving a square root

Even the progressive character of the tables turned out to be a failure: on two occasions (R. Johnson 8683 and C.K. Yang 9121) the world record was improved after just 9 events.

Quite expectedly, the pendulum was going to swing in the opposite direction and I am going to tell that story in the next post of the series.

When I decided to write the history of scoring for combined events I was faced with a major problem. How can one find the tables from 1952, 1934 and before? The oldest tables I had in my possession where those of 1962. And it had not been easy to obtain them. As the faithful readers of the blog know, I have been a scoring buff since my childhood. At some point, in the mid 60s, I set out to find the official scoring tables and went to the headquarters of the Hellenic Athletics federation. I met the person responsible for statistics, who received me with visible mistrust, his only remark being that the tables are copyrighted. At least he let me copy the address of the IAAF headquarters. Thus several years later, already living in France, I asked a british colleague to buy me a copy of the tables whenever she happened to be in London. (Things have become much simpler since that time). Still, the question remained on how to obtain the old tables.

Fortunately I had, over the years, a few contacts with B. Mallon, the well known Olympic historian (nobody is perfect) and I asked him whether he had copies of the old tables. He did and he graciously provided me of copies of all the tables that had been in use up to 1985. Thus I could set upon writing this series on the history of scoring.

No comments:

Post a Comment