In a recent twitter thread Ross Tucker (a physiologist for whom I have a great respect) addressed the question of testosterone and the way it has been used in order to formulate policies for DSD and trans athletes. To my eyes his explanations settled once and for all the question (although the question of how one can deal with DSD and trans athletes is far from settled). Thus I decided to write a post presenting his ideas. But before doing this it is important to summarise the situation (although I have, on several occasions, written posts on this burning subject).

To my eyes women's sports, and in particular athletics, is something sacred that we should strive to preserve at all costs. I understand perfectly that men should be allowed to decide to pursue their lives as women, if this would bestow them a better equilibrium. I respect totally such decisions, just as I do for the opposite ones, women who decide to live as men. However I draw the line in the case of sports. A man should never be allowed to participate in women's competitions. Tucker explains perfectly the rationale behind this. While the case of transgender athletes is not negotiable, the case of DSD athletes is more complex.

In my post on sex verification I told the story of how, over the past century, there have been several occasions where misguided sport managers have tried (in some cases with success) to have men compete in women's events. Today, such an outright dishonest behaviour is practically impossible. But, unfortunately the peril for women's athletics is even bigger. It comes under the acronym DSD, that stand for Differences in Sexual Development. It is the politically correct version of what was called before "hyperandrogenism".

Hyperandrogenism is a medical condition characterised by high levels of androgens. DSD is a more complicated situation and refers to congenital conditions affecting the reproductive system, in which development of chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomical sex is atypical. Persons with DSD are often referred to as "intersex". The case that introduced hyperandrogenism to the athletics vocabulary was that of C. Semenya.

I don't know how many times I have written on Semenya (too many) but, for the possible newcomers to this blog, I would like to summarise the situation.

Semenya came into the limelight when she won the 800 m in the 2009 World Championships with 1:55.45, a year-over-year improvement of her personal best by almost 9(!) seconds. The reactions didn't take long, the IAAF was constrained to launch an investigation and it resulted that Semenya was intersex. The counter-reactions did not take long either. The IAAF was accused of racism and imperialism. It goes without saying that I find these arguments scurrilous: the intersex condition of Semenya has nothing to do with the fact that she is black and african.

Anyhow, Semenya was cleared to participate in women's competitions and she went on to win the 2011 and 2017 World championships as well as the 2012 and 2016 Olympics (to say nothing of African Championships or Commonwealth Games). In 2015 the IAAF introduced the testosterone rule aiming at blocking hyperandrogenic females from competing with non-hyperandrogenic women. Following an appeal of D. Chand, the CAS invalidated the rule allowing Semenya to participate in the 2016 and 2017 competitions. (Chand also profited from this in order to participate in major competitions, including the Olympics, her major success being a gold medal over 100 m in the 2019 Universiade).

The IAAF's petition to the CAS decision was re-examined in 2018 and a new testosterone rule was introduced forbidding participation to hyperandrogenic women in the events spanning the distances form 400 m to a mile. Semenya's appeal was rejected in 2019 limiting her choices to either undergo a pharmacological treatment in order to bring down her testosterone levels or move to longer distances. (She tried the latter without success). F. Niyonsaba, who won silver in Rio and London in the 800 m, being of a much lighter frame than Semenya opted for the longer distances where she has now personal bests of 14:25.34 in the 5000 m and 30:41.93 in the 10000 m. In Tokyo she was disqualified in the former distance during the semi-final, otherwise she would have certainly obtained a place on the podium.

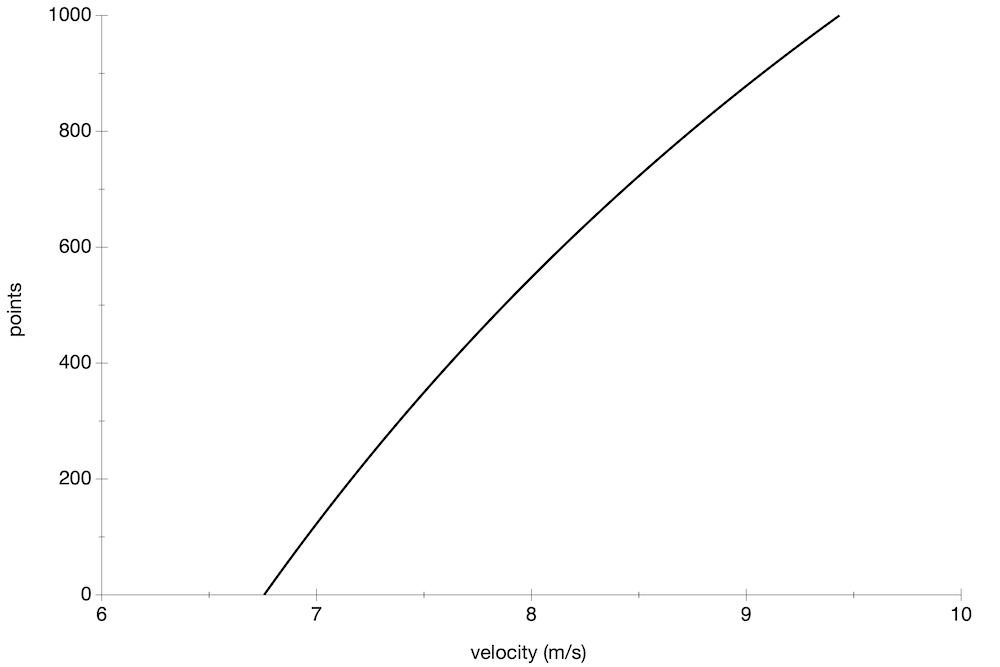

It was another DSD athlete who drew all the media attention in Tokyo. Early in the season, there were news of two 18 year old namibian athletes who registered fantastic times over 400 m, Christine Mboma and Beatrice Masilingi: 49.53 and 49.22 s. And then the verdict was handed down: both namibian teenagers were hyperandrogenic. Thus they were not allowed to race the 400 m any more. (Mboma's out-of-this-world time of 48.54 s was not homologated). Unfazed they converted to 200 m runners and went on to participate in Tokyo's olympic final where Masilingi was 5th (with 22.18 s) and Mboma second with an incredible 21.81 s personal best.

World Athletics is watching from the sidelines, Sir Sebastian having stated that Mboma's success suggests that the testosterone rules are vindicated. And when asked whether Mboma could break the world record he replied that this “probably” would then give the governing body more questions to contend with where the rules are concerned.Before presenting Tucker's arguments let me remind you what does the "testosterone rule" stipulate (restricted events being the distances from 400 m to the mile including, hurdles relays and combined events):

If a female athlete wishing to participate in a Restricted Event at an international competition has a DSD that results in levels of circulating testosterone greater than 5 nmol/L, and her androgen receptors function properly, such that those elevated levels of circulating testosterone have a material androgenising effect, she must reduce those levels down below 5 nmol/L for six months (e.g., by use of hormonal contraceptives) before competing in such events, and must maintain them below that level until she no longer wishes to participate in Restricted Events at international competitions.

Without further ado that's what Ross Tucker has to say.

Testosterone and performance has become a kind of fixation, but testosterone level per se is not the right place to look. Testosterone is the driver of the differences between men's and women's performances and so sports tried to use this cause-effect in order to exclude people from women's category.But women's category in sport exists to exclude people who experience androgenisation during puberty and development.

People think that reversing T levels will remedy this. This is misguided. Once androgenisation has occurred it's too late. Some changes are irreversible, other only partly reversible and only a few can be undone. Lowering testosterone levels does not bring fairness into sport because testosterone has already done the work, primarily in puberty.

A "snapshot" of testosterone levels cannot be related to performance. And thus it is misleading. The important thing is whether androgenisation has occurred and testosterone levels are an excellent guide to whether it has or not. What matters is whether testosterone is high or not, the actual level is not important.

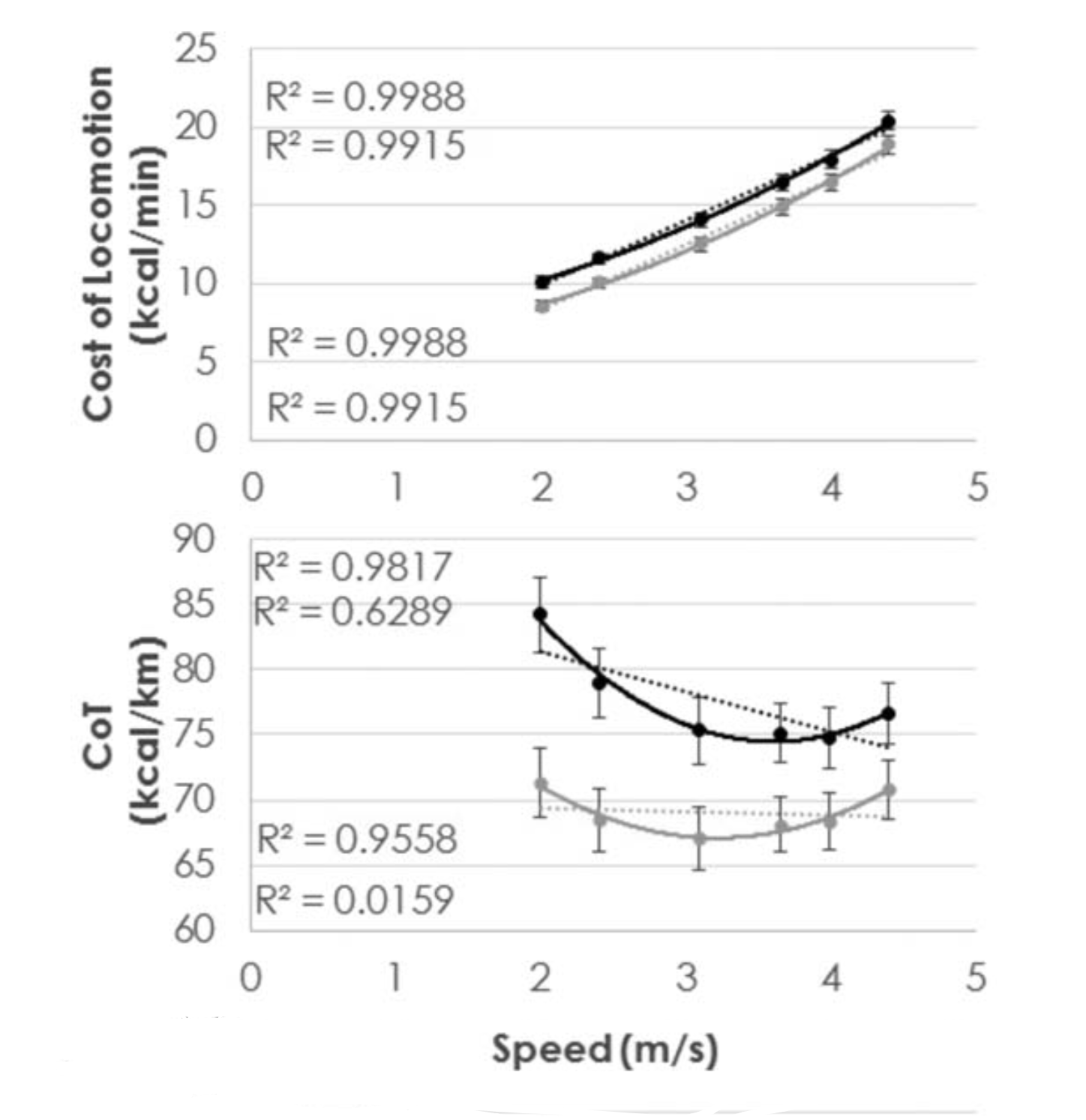

Here Tucker gives a great example. Measured VO2max does not correlate with marathon performance. All good marathoners have high VO2max. You need a high value to become a good marathoner but once you are there, there are other things that count. Of course there are people with not-high VO2max. They cannot become good marathoners.

So, the presence of high level of testosterone during life plus the ability to use it for androgenisation is the important thing. Androgenised people are in male category, unandrogenised are in female category. Lowering testosterone levels does not allow a male to become female.

Some male can be non-athletic and, were they to compete with women, they would be beaten. This is the same phenomenon as when an able-bodied athlete sneaks into a disabled category and still loses. But this failure does not invalidate the essential difference between categories.

And when people asked the question on how to implement segregation, Tucker replied that it should not be based on testosterone levels but rather on biological sex.

That was the clearest discussion of the testosterone effect on performance that I have ever seen.

I am appalled by the fact that right now we are ready to sacrifice millions of women athletes in order not to look unfair towards the one transgender male who decided that, since he could not beat men, he would try his luck against women.

But then we are living in an era of woke-ism and these things should not astonish me any more. For the time being we are in the middle of an assault, in the name of fairness towards (erstwhile) oppressed categories, against what women have obtained through their hard-fought battles over more than a century, namely an equity in sports. Is there any hope for rule changes that would guarantee fairness in women's competitions?

When questioned, Lord Sebastian did not rule out the possibility of looking at the DSD rules governing other distances: “My responsibility, as uncomfortable as it is, is always to do whatever I can to maintain the integrity of competition and that level playing field. We’ve never said that there may not be advantages at lower levels elsewhere”. He also suggested that different classifications might yet come into sport in the future – including an “open” category for almost everyone and a restricted “biological female”. “I don’t think that’s where most of my council are at the moment,” he said. “But this is a debate at the moment. I’ve heard coaches and people who are interested in the sport, and more broadly from the sport, have discussed that”.

Meanwhile, the WA site goes into ecstasies over C. Mboma's performances.