Those who read regularly my blog know that I do not like the triathlon. I find the formula, where the stopwatch is running continuously, somewhat unnatural, in particular for short events like the olympic one. The athletes must manage the change of attire and equipment, between swimming and biking and again between the later and running, losing the least possible time. In an event of, roughly, 50 km where the best athletes are taking well below 2 hours, the loss of one minute during equipment change can easily modify the outcome. But, of course, when compared with the supposedly "modern" pentathlon the triathlon is infinitely more interesting.

Now, to be fair, my objection concerning the transition time from one specialty to the other is no more valid when it comes to the original triathlon formula, the Ironman. In an event that takes 7-8 hours to complete, the transition time is negligible. Talking about the Ironman as the "original" triathlon needs some explanation. It is true that the first competition over the Ironman distances (3.8 km swimming, 180 km of bike and running a marathon) took place in 1974 and the name was coined in 1978 with the creation of the Hawaii triathlon. However the very idea of a swim-bike-run event can be traced back to France and the beginning of the 20th century with the famous « Course des Débrouillards ». The names « Les trois sports » and « La course des Touche-à-tout » were also used and sometimes the swimming was replaced by canoeing. (Were I a fan of triathlon, I would have inserted a « cocorico » here).

How did I end up writing about the triathlon? As you may remember I published recently two articles on Ultra-running and the Speed Project, both having to do with running events that stretch over several days. While researching for the latter post I stumbled upon an article, mentioning the fact that some canadian lady athlete had just completed a Deca Ultra-triathlon in 11 and a half days. I read the detail and I could not believe my eyes. The event consists in 10 Ironmans lumped together: 38 km of swimming, 1800 km of biking and 10 marathons. I decided to learn a little bit more about these crazy events and I found out that the "deca" is not the last word. What started in 1985 as a double Ironman (or was it the 1983 Ultraman that launched the ultra-triathlon events?) has been steadily expanding with, today, 20x and 30x events. And the two formulae do exist, a continuous one and a "one per day".

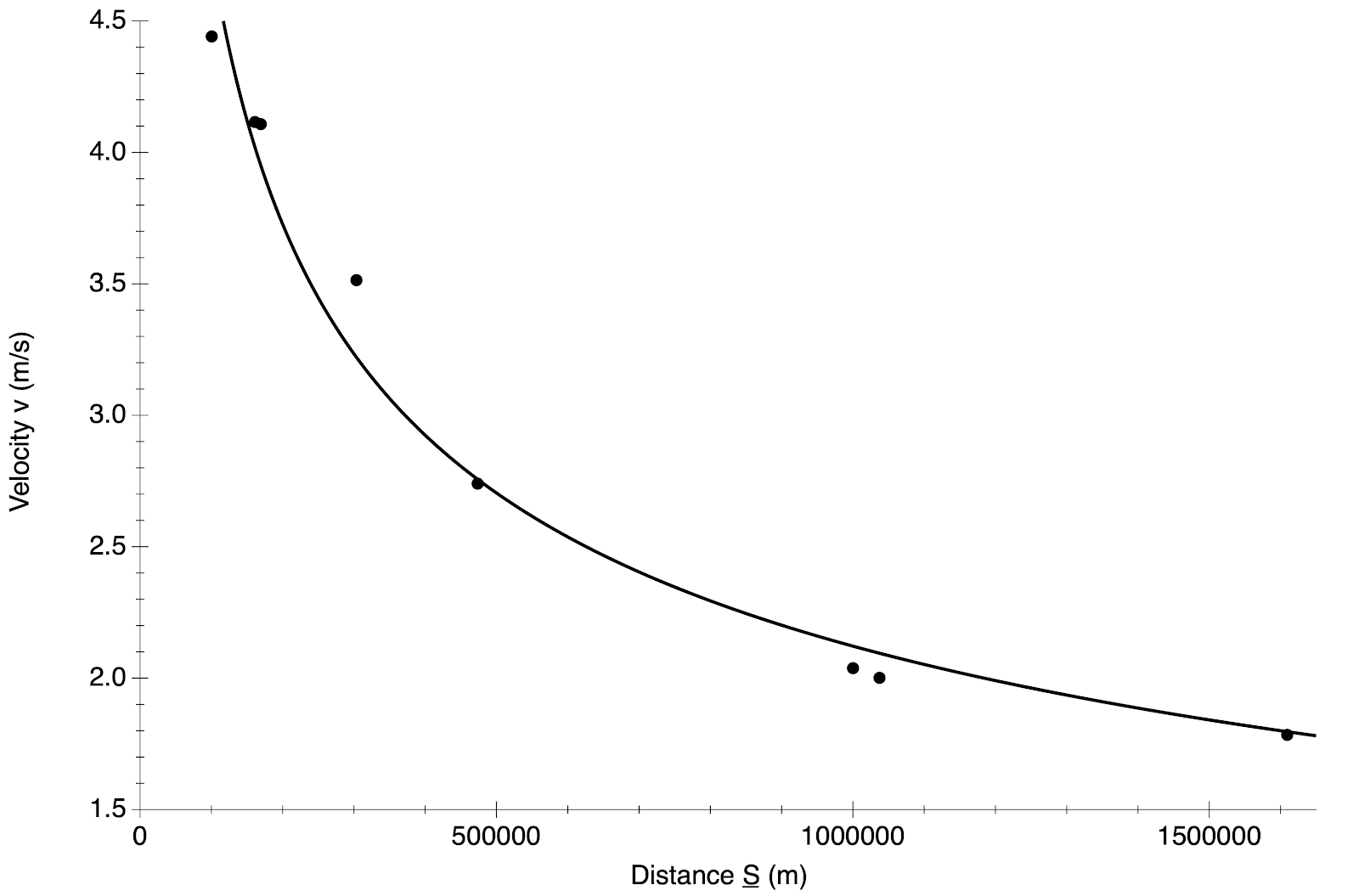

When I saw the performances of the triathletes in events spanning up to 40 days I was immediately reminded of my work in collaboration with J. Meloun and G. Purdy (A mathematical model for scoring athletic performances, Math. and Sports 5 (2023) 1) where we analysed the running velocities for distances going from 20 m to 1600 km. As explained in my post on running velocities, for multi-day events the additional slow-down mechanism is due to the fact that the athlete must take time to sleep, eat and take care of other bodily functions. And, in fact, for races with duration above 12 hours, a non-negligible amount of time is devoted to non-running moments. In our paper mentioned above, we had presented a fit of the velocity as a function of the distance for various ranges of distances. The one that is interesting here is one covering the distances from 100 to 1600 km, for durations from roughly 6 hours to over 10 days. In the figure below I present the data together with the best fit of the form

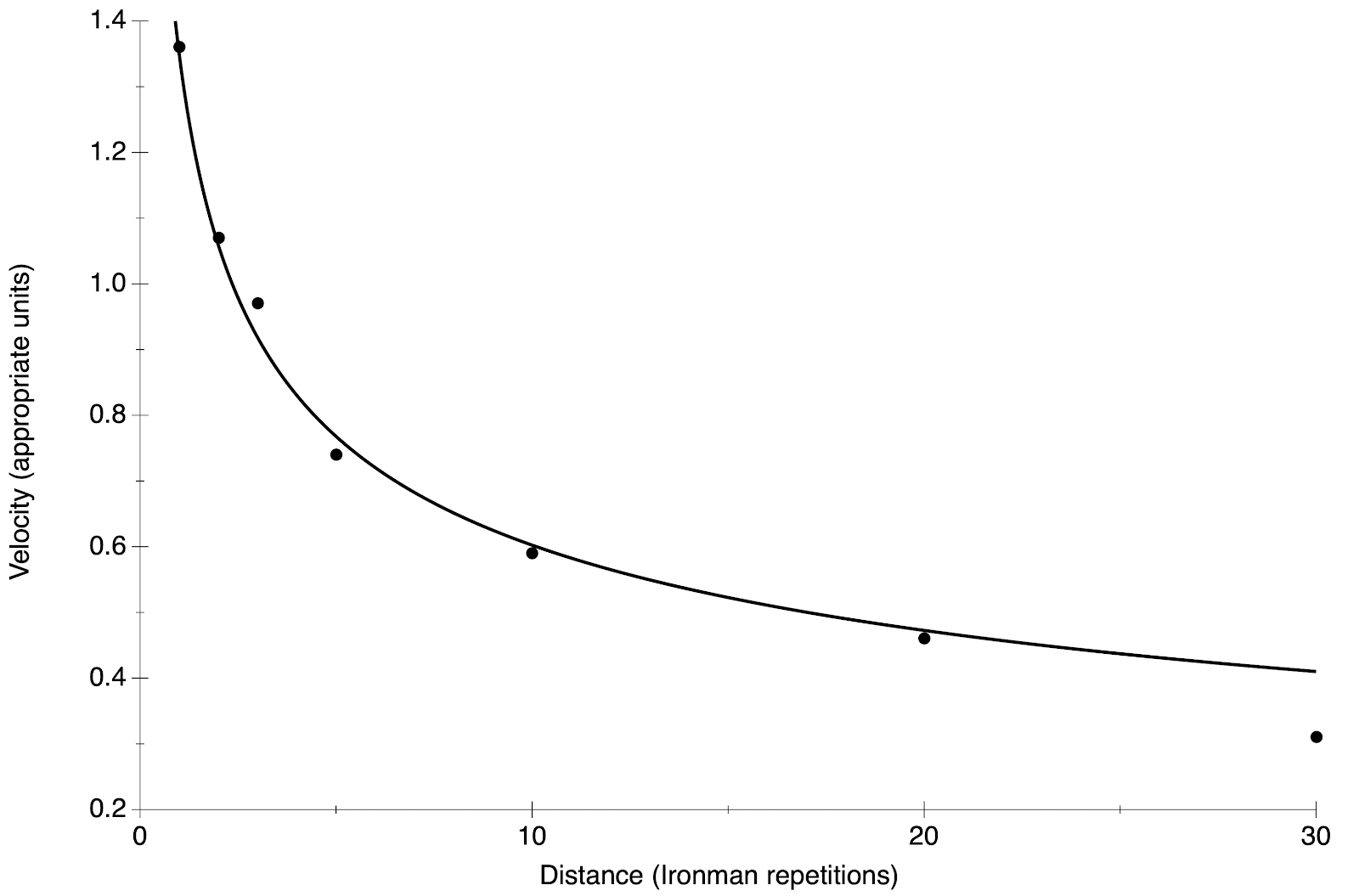

Next I turn to the ultra-triathlon data, plot the velocity (in the appropriate units) as a function of the repetitions of the Ironman and fit the date with the same formula and with the same exponent γ. (The choice of units affects the value of A but not that of g).

We can remark that the fit is quite satisfactory. Thus we may conclude that the ultra-marathoners and the ultra-triathletes face the same difficulties linked to the excessive duration of the event and the fact that they must reserve time for sleep and other body's needs. It is also telling that in the case of the triathlon the fit over-estimates the velocity for the 30x event. Since the event requires more than a month to be completed it is natural that long-term fatigue sets in with as a result a further velocity degradation. One should compare this to the fit we presented in the article mentioned above for the velocity as a function of the distance for distances from 1 km to the marathon. There, the exponent gamma is much smaller, around 0.07. Ij this case the velocity degrades very slowly, in a mechanism remaining predominantly aerobic over the whole span of distances, the decrease being due mainly to the onset of fatigue.

When I set out to write this article I was a triathlon-skeptic. After having read several articles on the origins of the discipline and on its "ultra" forms I am less so. But, let's be frank, I am nowhere near becoming a fan. One reason for this that the triathletes I am meeting are invariably as...les, considering themselves as "ironmen" despite their obvious mediocrity. People who run know very well that it's not because they managed to finish some marathons that they may consider themselves on par with Eliud Kipchoge. This is a lesson that triathletes have yet to learn.

No comments:

Post a Comment