I have always pointed out in this blog that World Athletics is doing something the wrong way: scoring track events using time instead of the appropriate physical variable i.e. the velocity.

Recently the World Athletics Scoring Tables were updated in order to provide scoring for the "new" events recognised by WA: 300 m hurdles, mile road race, half marathon race walk, marathon race walk and the mixed relays 4x400 m outdoor and indoor. Mind you, these are not the combined events scoring tables. (I don't know how long we will have to wait before World Athletics decides to provide a scoring for women's short track 1000 m making possible the homologation of indoor heptathlon records for women).

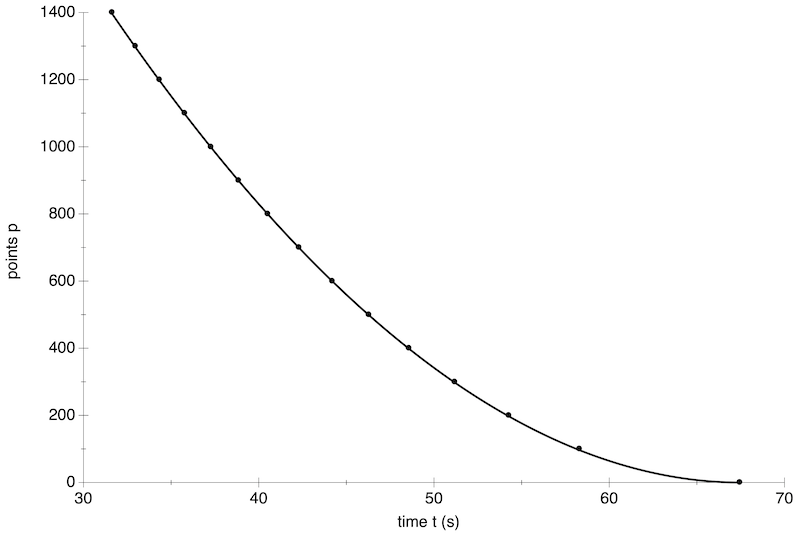

Since the 300 m hurdles has been a race abundantly advertised at the beginning of the season I decided to have a look at its scoring. Below is a graph giving the dependence of the number of points of the registered time.

The continuous line corresponds to the fit with a formula

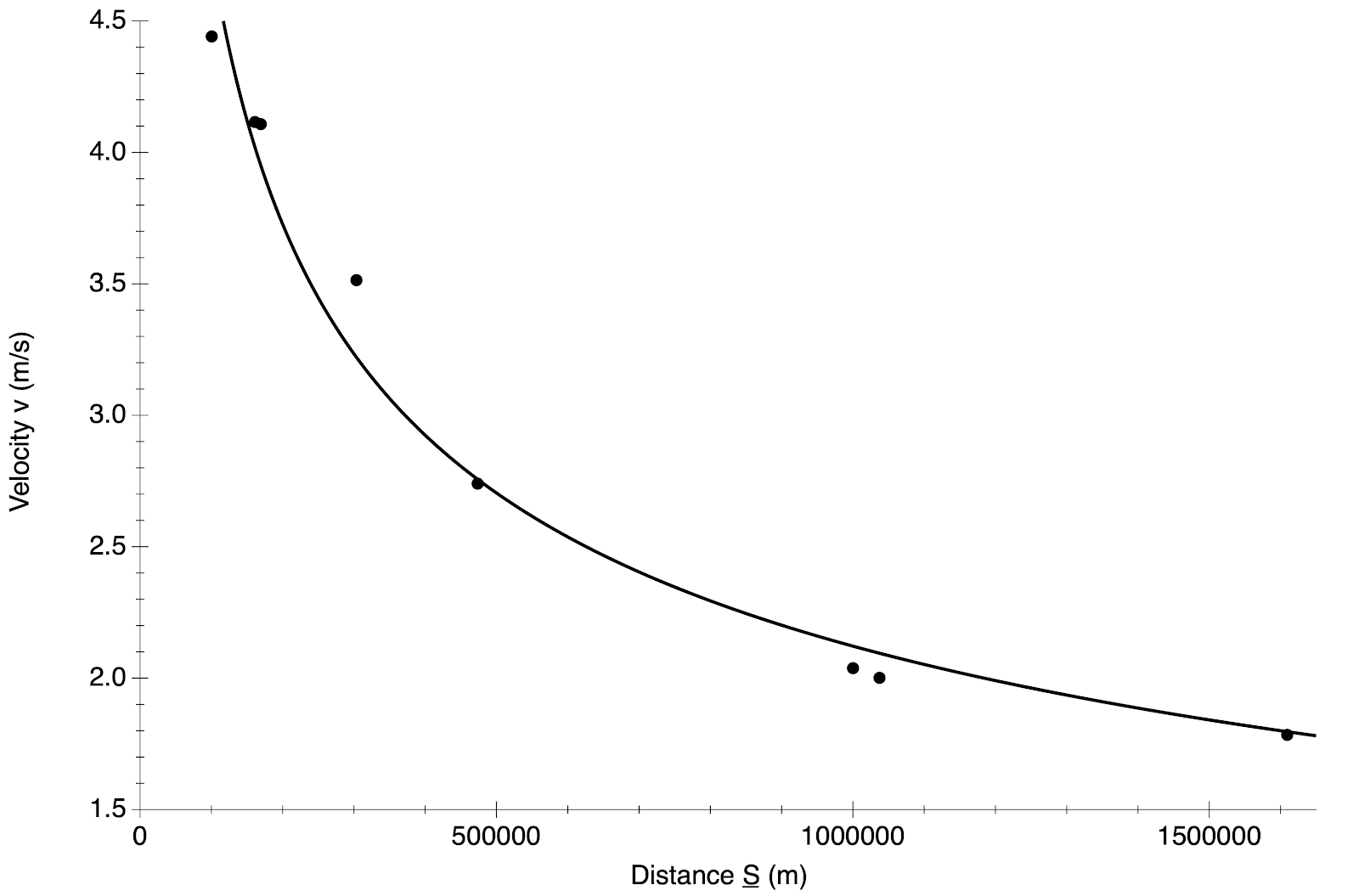

(which is exactly what WA is using in the decathlon scoring tables). From the best fit we obtain the values a=1.279 and c=1.955, while the time corresponding to 0 points is 67.42 s. The appearance of the curve and the value of c close to 2 sustain the illusion of progressivity. But let us look at what happens when one uses the proper physical variable, namely the velocity. In the graph below

the dependence of the number of points with the velocity is almost rectilinear. In fact when one performs a fit with an expression

one obtains the values a=222.7 and c=1.129 (while the velocity for 0 points is 4.4776 m/s). The value of c close to 1 confirms the visual impression of lack of progressivity.

This is not something new. The same behaviour is observed on the scoring of all track events. But, by giving the scoring in terms of the time, a misleading progressivity appears, which unfortunately masks the defect of the scoring choice.

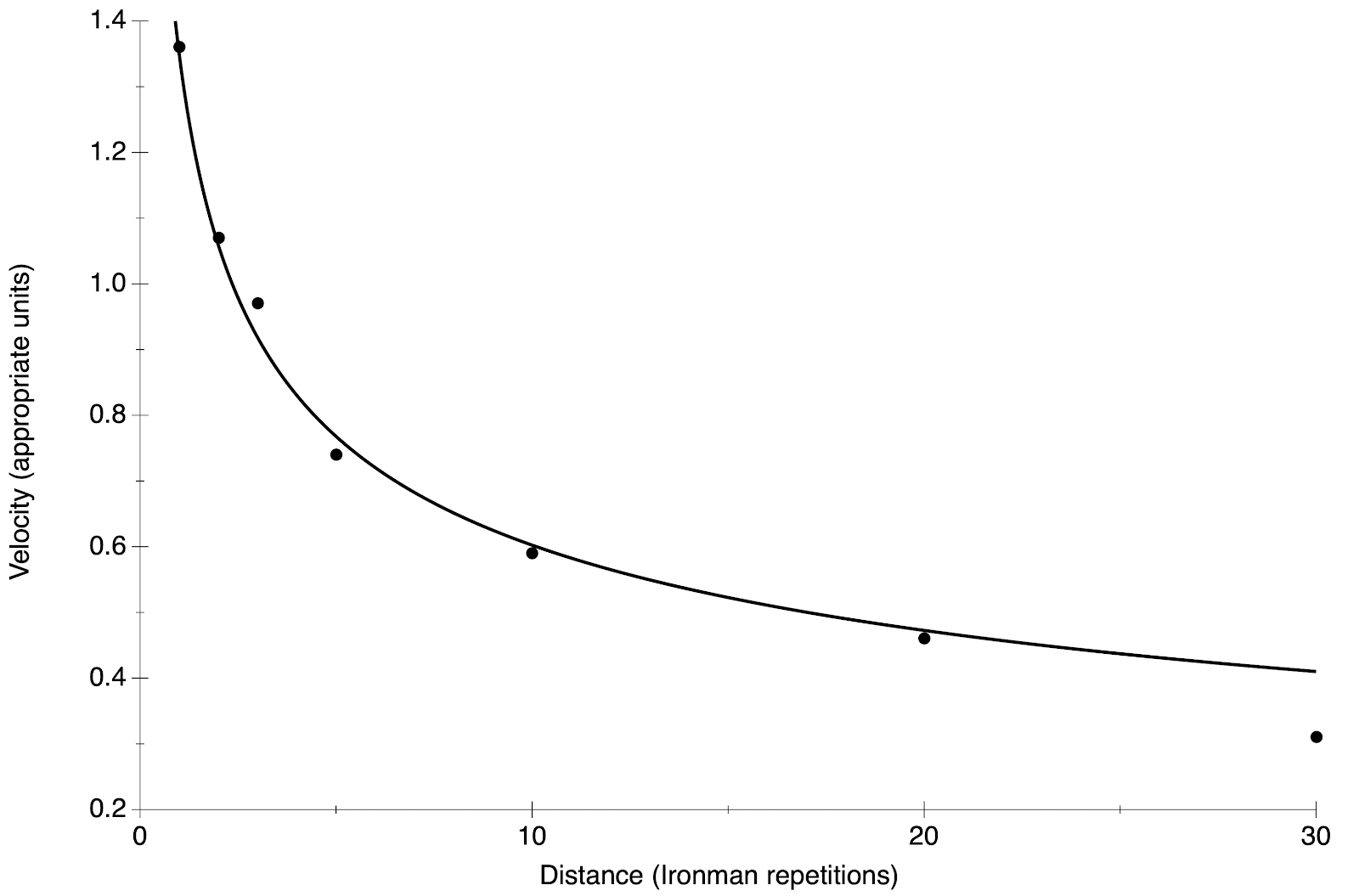

The question of progressivity is one that my friends of Décapassion, Frédéric and Pierre Gousset, have addressed in a slghtly different context, that of throws. They remarked that the scoring of throws, given by a formula similar to the one based on the velocity, has exponents c equal to 1.05, 1.1 and 1.08 for the shot put, discus and javelin throw respectively, an almost rectilinear dependence. They argue that this should be remedied with exponents c=2 leading to real progressivity. I will not enter into more details here and invite you to go and read their most interesting article. (We have been, for some time now, thinking about writing a joint article on the matter. I just hope that one day we'll find the time to do this).