Or how the rigmarole ended: not with a bang; it just fizzled out

In 1972 Baron Killanin (yes, another baron) was elected at the presidency of the IOC. Contrary to his predecessor, he demonstrated intellectual flexibility and one of the first issues he addressed was that of the amateur eligibility.

The first attempt at modernisation did not yield substantial results. Still, everybody agreed to drop the requirement that athletes “be engaged in a basic occupation to provide for their present and future”. The limits of days an athlete could devote to training was lifted coupled to broken-time payments. But all those were token reforms, since they just acknowledged practices that were already in place (albeit ones to which everybody turned a blind eye).

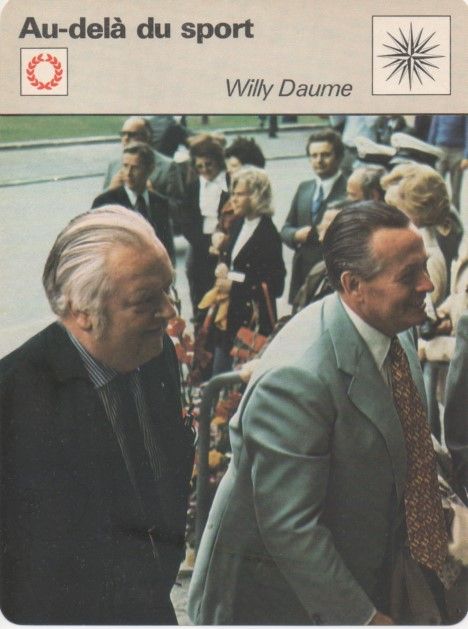

The real changes came when W. Daume (the organiser of the 1972, Munich, Games) was appointed chairman of the eligibility commission in 1978. In his first address he reminded the IOC members of some basic facts that were voluntarily forgotten: the ancient Greeks were not amateurs and, in fact, de Coubertin himself did not give a damn about amateurism.

In an age where the IOC was going to rake in millions, it was dishonest and hypocritical to ask the athletes to make sacrifices. And with millions dangling in front of them, the IOC dignitaries were not going to stick to asceticism for the sake of amateurism.

But another danger was lurking. The whole olympic ideal was based on the catchy Citius, Altius, Fortius maxim. But “Higher, Faster, Stronger” implied specialisation and a scientific approach to training. After WWII the science of sport exploded with research in every possible direction. Among the latter, that of pharmacological assistance of training was prominent. The eastern European countries were the pioneers in this domain, with GDR becoming the indisputable champion. Western countries followed suit, the US supporting doping both officially and unofficially. The IOC had to do something about that and antidoping rules were introduced, the enforcement of which was entrusted to the medical commission.

In 1981, Daume proposed a more liberal eligibility code: "the Olympic Movement, which expects athletes to pursue excellence, should not discriminate against or exploit the full-time athlete because of that excellence”, he said. Curiously the ones who opposed the more lax amateurism code were the eastern European countries. This is easily understood, since the state support to athletes in those countries was akin to professionalism. With a good measure of anticommunist feelings the president of the AAU remarked that "the marriage of convenience between communists and Brundagian amateur ideologues resembles to the same unholy alliance you find when the bootleggers and the clergy combine their votes to maintain prohibition”.

The main merit of Lord Killanin is to have appointed W. Daume to the chairmanship of the Eligibility Commission. In fact some believe that Daume's intervention in Munich, prior to the vote for the IOC presidency, where he implored the IOC members to reform amateurism, because eligibility rules forced athletes “onto a path of untruth and destroys the belief in the entire Olympic movement”, could have been instrumental in Brundage not seeking another term.

Lord Burghley, who had lost to Brundage in the 1952 election for the IOC presidency, remarked in 1980 that “professional sport was a perfectly reasonable way of earning a living”.

In 1980 J.A. Samaranch succeeded Killanin (a Marques succeeding a Baron). While Killanin had been treading lightly during his mandate, Samaranch did not hesitate. He worked to secure the financial prosperity of the Olympic Movement, transforming the IOC into a full-fledged corporate entity. The challenge for the IOC was substantial. While they were ready to grant the international federations a liberal eligibility code, they insisted that there was no place in the Olympic Games for professionals. But this was also going to change. And that was going to happen under Samaranch's reign.

No comments:

Post a Comment