Or how the social marketing of de Coubertin led to a century-long dictatorship in sports

I have written on several occasions about our beloved Baron and how, in the quest of self-aggrandisement, he deformed the olympic ideals. In a recent article of mine I told the story of de Coubertin's successor, the Comte Baillet-Latour, and how, under his presidency, the amateurism obsession reached new heights. While researching the Baillet-Latour article, I came across publications that were dealing with the amateurism question. I dug deeper and finally I decided to write a short series on the question.

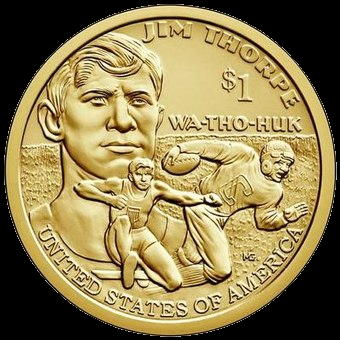

De Coubertin and Baillet-Latour are definitely to blame for the harm of amateurism to sports. Both were old-school aristocrats and one can understand (but certainly not condone) their attitude. And to tell the truth, during the years of their presidency, the finances of the International Olympic Committee were more than shaky. With the advent of television in the 60s things did change and the IOC started making money out of the Olympics. But A. Brundage, who held the president's position at that time, insisted on imposing his anachronistic ideas of a sport reserved to amateurs. I told the story of Brundage in an article of mine and so I am not going to repeat it here. I will just, once more, mention the injustice to one of the greatest athletes of all times, J. Thorpe, in which Brundage played an important role.

In my article on Brundage I wrote

There is no indication that Brundage had played a role in that initial disqualification of Thorpe. However where he did indeed play a major role was in refusing vehemently, throughout his stint as IOC president, the rehabilitation of Thorpe.

But let us tell the story of Jim Thorpe, immolated at the altar of the false-god of amateurism.

Thorpe won the pentathlon and the decathlon in the Stockholm 1912 Olympics dominating both events like nobody had done before (or has since). Thorpe had been a student at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School from 1904 to 1913 (although not continuously). After his victory in Stockholm he went back to the school to play football. That was the beginning of the end.

In a post-season demonstration tour, a chance remark by one of Thorpe’s former coaches, C. A. Clancy, revealed to a local reporter, R. Johnson, that Thorpe had played two summers in the league, in 1909 and 1910, earning a few dollars per game. Johnson printed the story in a local newspaper in January 1913. Clancy denied the facts but, a few weeks later, the story made the national newspapers. And the president of the American Amateur Athletic Union, J. E. Sullivan, decided to personally oversee the handling of the affair. Those who follow closely my blog may remember that Sullivan figures prominently in the Gallery of Shame, for his misogynistic attitude. Llewellyn and Gleaves in their book on Olympic Amateurism point out that Sullivan had earned a small fortune peddling Spalding sporting goods.

The Thorpe case offered Sullivan a chance to restore his reputation and counter longstanding allegations that the AAU openly sponsored professionalism. Sullivan promised to leave no stone unturned in investigating the allegations. Well, it took him all of one day. There was no trial, no investigation, and no hearing. Thorpe had no money, no lawyer, and no opportunity to mount a defence.

The situation became somewhat embarrassing for the IOC, since the deadline for the validation of the results of the Olympics was long past. (In fact that was the hypocritical argument for the reinstatement of Thorpe in the 80s). But Warner presented them with a fait accompli: he went to Thorpe's house, took the medals and shipped them back to Stockholm.

Stripped of his titles, Thorpe turned professional and had brilliant careers in baseball, american football and basketball. Over the years the supporters of Thorpe fought to have him cleared. The IOC systematically refused, with A. Brundage rebuffing several attempts, claiming that "ignorance is no excuse". In fact, the disqualification of Thorpe had been quite convenient for Brundage. With Thorpe removed from the amateur ranks, Brundage became national all-around champion, a standing that he later admitted helped open doors to his construction business. A self-righteous, vindictive personality, Brundage, although, most probably not involved in the original disqualification of Thorpe, played a major role in the dismissal of the pro-Thorpe petitions. Is it curious that the AAU voted to reinstate Thorpe’s amateur status, in 1973, just after Brundage retired?

In 1982 the IOC relented and reinstated Thorpe, but only as co-winner(!) of the two combined events. And it was only in 2022 that justice was finally done and Thorpe was declared sole winner of the two events. So except for his two Olympic titles, Thorpe earned another, totally unenviable, title, that of being the first athlete charged, convicted, and punished for violating the IOC’s amateur regulations. What regulations we are talking about, that is far from clear. In fact, de Coubertin was rather embarrassed by the situation and declared that it was time to revise the regulations on amateurism. After several attempts at a coherent formulation of rules (de Coubertin floated also the idea of an amateur oath) and the creation of an international amateur license, the IOC threw in the towel and in 1914 voted to empower the international federations with the task of governing amateur eligibility.

The amateurism farce was just beginning.

No comments:

Post a Comment