Last year I ran across an article in the Big Dog's Backyard Ultra. The term "backyard ultra" was familiar to me, since four years ago I published an article on the "Quarantine Backyard Ultra race". I read the article and I must say that I was impressed. So, I decided to learn more about this crazy event.

Let's start with the rules.The athletes run on a loop which must be 6705.6 m long.

In case you wonder where this crazy measure came from, well, it has, once more, to do with those pesky imperial measures. And, no, the length is not a round number in miles. It was calculated so that 24 repetitions of the loop add exactly to 100 miles. You can now guess where this 24 comes from.

The athletes start at precisely every hour.

Each loop must be completed within the hour.

The winner is the last person to complete a loop.

This last point has as a consequence that if nobody can complete an extra loop there is no winner to the event.

I don't think it can get crazier than this. The participants have to run and run and run till they are unable to go on. And the last one to stand, when all the others have fallen, wins. This sounds like the dance marathons that had flourished during the Great Depression in the 30s. (If you wish to learn more about the dance marathons of the 30s I suggest you read this article. It is more entertaining than the Wikipedia one).

Last year's Backyard Ultra competition resulted in a new record of 450 miles covered in 108 hours. Just do the maths: 108 hours means 4 and a half days. Without sleeping!

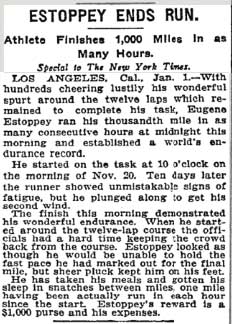

While perusing the Wikipedia article on the Backyard Ultra I saw a photo of a precursor of ultra races, one Eugene Estoppey who, in 1910, ran one mile per hour for 1000 hours (that's over 40 days). He managed this by sleeping for half an hour at a time although he did not total much more than four hours of sleep every day. He had a respectable personal record of 4:40 on the mile and he ran the first of his hourly miles in 5:35. His completing successfully his endeavour was celebrated by an article in the New York Times.

From Wikipedia I jumped to the Ultrarunning Magazine and an article on Estoppey by J. Oakes. What attracted my attention was a note at the end of the article with a reference to an older one by P. Lovesey, a historical article on 19th-century running feats. Unfortunately, the article is behind a paywall. However, the top of the article is visible, as a teaser, and I could read that Ron Grant had just completed a 1000-hour run where he covered 2.5 kilometres every hour.Is the 1000-hour race the longest one? Apparently, not. The Trans-America footrace is way longer, with runners covering more than 5000 km. The current record is held by Robert Young in 482 hours and 10 minutes, covering 5032 km from California to Maryland. And, in case you were wondering, women are also participating in those crazy events, the record being held by Jennifer Bradley in 720 hours and 27 minutes for 5316 km (where she finished less than one hour behind the winner of the event who holds the record for the San Francisco-Key West race).

Reading all those articles on ultrarunning I must say that I am amazed by the suffering that people are ready to inflict upon themselves. But, still, I find the 100+ hours of sleepless continuous effort mind-boggling. And, I just found out that the record of sleep deprivation is slightly longer than 11 days or almost 19 days, depending on your sources. But this is taking us too far from the scope of this blog so I prefer to stop here and let you hunt down (if you are interested) these sleep deprivation experiments. But, reading them, I am now convinced that we have not yet reached the limit of the backyard ultra performances.